Celebrating Winter Solstice

Updates from the Japanese Countryside

Happy winter solstice to all those in the Northern Hemisphere. A day that welcomes the shortest and darkest day of the year. A day where we turn inward and welcome a moment of stillness—literally sol (“sun”) and sistere (“to stand still”).

As everything living exists in an interconnected ecosystem of life cycles, we can, too, embrace a quieter, stiller, and darker moment of the year to pause and reflect.

In Japan, the winter solstice is known as toji 冬至, where 冬 is the kanji for winter and 至 is the kanji for arrival. The winter solstice is celebrated as a marker of harmony—a balancing point between the ‘yin’ of darkness and cold and the ‘yang’ of warmth and light. Exploring the concept of balance is a lifelong journey, and I feel like days like these are a poignant reminder of how nature exemplifies balance.

The cold finally arrived in Japan a couple of weeks ago, following an unusually warm autumn. The leaves have changed color, and the citrus trees are now glowing in shades of bright yellow and orange.

The last time I wrote on Substack was back in June, as the summer heat began to rise. Now, as winter envelops us, it feels like the perfect season to slow down and come back to this space.

Winter truly feels like the right time for finding comfort in words written and read. There’s something about this period of year that invites us to appreciate the small, quiet moments around us and let our thoughts settle gently, like a leaf drifting from branch to ground. Maybe the holiday season feels like the exact opposite for you—busy and intense—but it’s in these moments, stillness becomes an even greater gift.

Winter Solstice Traditions 冬至の伝統

In Japan, the winter solstice is celebrated in many small ways, like soaking in a hot bath with citrus, often yuzu, which has a heavenly fragrance, to warm the body and protect against illness. Across Asia, many cultures practice rituals that lend to health and a sense of renewal.

There are also specific foods that are associated with Japanese winter solstice such as the kabocha squash. In the past, when vegetables were scarce and winter months were much more harsh, kabocha was a rich source of nourishment.

There’s something so hearty about kabocha squash—naturally sweeter and more savory than a butternut squash. It reminds me of a natural cross between a sweet potato and a pumpkin. These rich, delicious dishes fill the body from the inside out with warmth. Itokoni いとこ煮 is a popular and symbolic 冬至 dish, made up of simmered kabocha and azuki (red beans). Other Japanese solstice foods in Japan are daikon radish, ninjin carrots, and a handful of other Japanese vegetables.

Happy 冬至!Happy winter solstice!

What I’m Reading

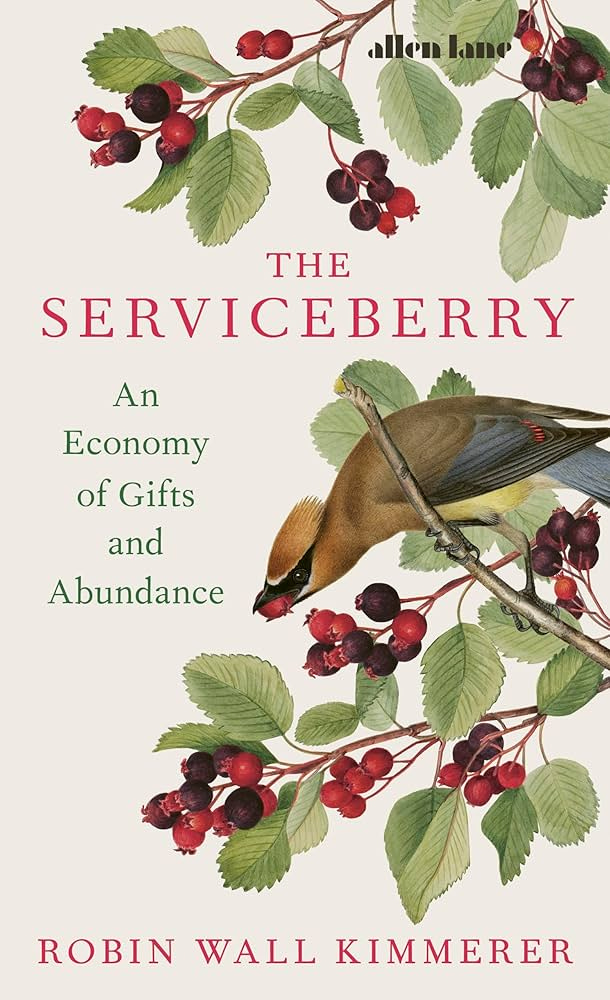

There’s no book more fitting for this season than Robin Wall Kimmerer’s recently published The Serviceberry. It’s a short and very easy read, with every paragraph leaving me feeling lighter and more grateful for the ways living in a small, rural community lends to her main themes of reciprocity and interconnectedness.

Gratitude is so much more than a polite “thank you.” It is the thread that connects us in a deep relationship, simultaneously physical and spiritual, as our bodies are fed and spirits nourished by the sense of belonging, which is the most vital of foods.

Gratitude creates a sense of abundance, the knowing that you have what you need. In that climate of sufficiency, our hunger for more abates and we take only what we need, in respect for the generosity of the giver. — Robin Wall Kimmerer

Kimmerer, an Indigenous scientist and botanist, weaves together insights from Indigenous wisdom and the plant world, much like in her previous book, Braiding Sweetgrass. While our modern economy often revolves around scarcity and competition, she offers the serviceberry as an example of a different way of relating to one another—one rooted in abundance, sharing, and mutual care.

Short Reflections

Four years ago, I moved to Kamikatsu, a small village in rural Japan. I knew so little about this place then, but each year, I’ve learned so much about Japanese culture through its people, seasons, traditions, and food.

The intended purpose of moving to Japan wasn’t entirely/only to connect with this part of my identity, but it has certainly has unfolded as one of the most meaningful parts of living in Japan. Being Japanese comes with nuances—some I love deeply, and others I question or challenge.

This newsletter began as a way to share glimpses of life in rural Japan—a lesser-told story in a world increasingly shaped by urbanization and convenience. These stories, like time capsules, capture moments of self-sufficiency and creativity: cooking from scratch, repairing what’s broken, and crafting by hand.

Simple traditions—making umeboshi pickled plums in spring, hanging kaki persimmons in winter—and community events like harvest festivals remind me of our deep connection to the land and the cycles of nature.

Looking Ahead

As this year draws to a close, I feel grateful for all that I’ve experienced and learned—and for the opportunity to share it here.

What would you like to see more of in the coming year? I’d love to hear your thoughts and ideas.

Here’s to many more stories and reflections—to savoring life’s small joys and its beautiful imperfections. Wishing you all a restful holiday season and a New Year filled with warmth.

With love,

Kana

My husband and I moved to rural Himachal, a state in India’s Himalayas, 7 years ago and so much of what you resonates! Learning about and participating in a culture that I’ve (it’s my home state) been divorced from till we moved here, the community and interconnectedness, the growing and sharing of some of our own food and the cooking from scratch, the local treatment of local foods… it’s all Magic!