Please feel free to listen to this post in audio-form (sound of rain in the background)

Beginning something new is always wonderful, but there is something beautiful in returning—in continuing. There’s comfort in familiarity, in picking up where you left off. I felt this when I went back to the small village of Kuo last week to make kancha tea for a second year in a row.

Making kancha last year was special for many reasons. The tea itself carries a unique story. I’ve always been drawn to the lesser-known, less-appreciated things in life, so when I learned about a tea made by a single elderly woman—one that few had ever heard of—I was immediately drawn to both the tea and her story.

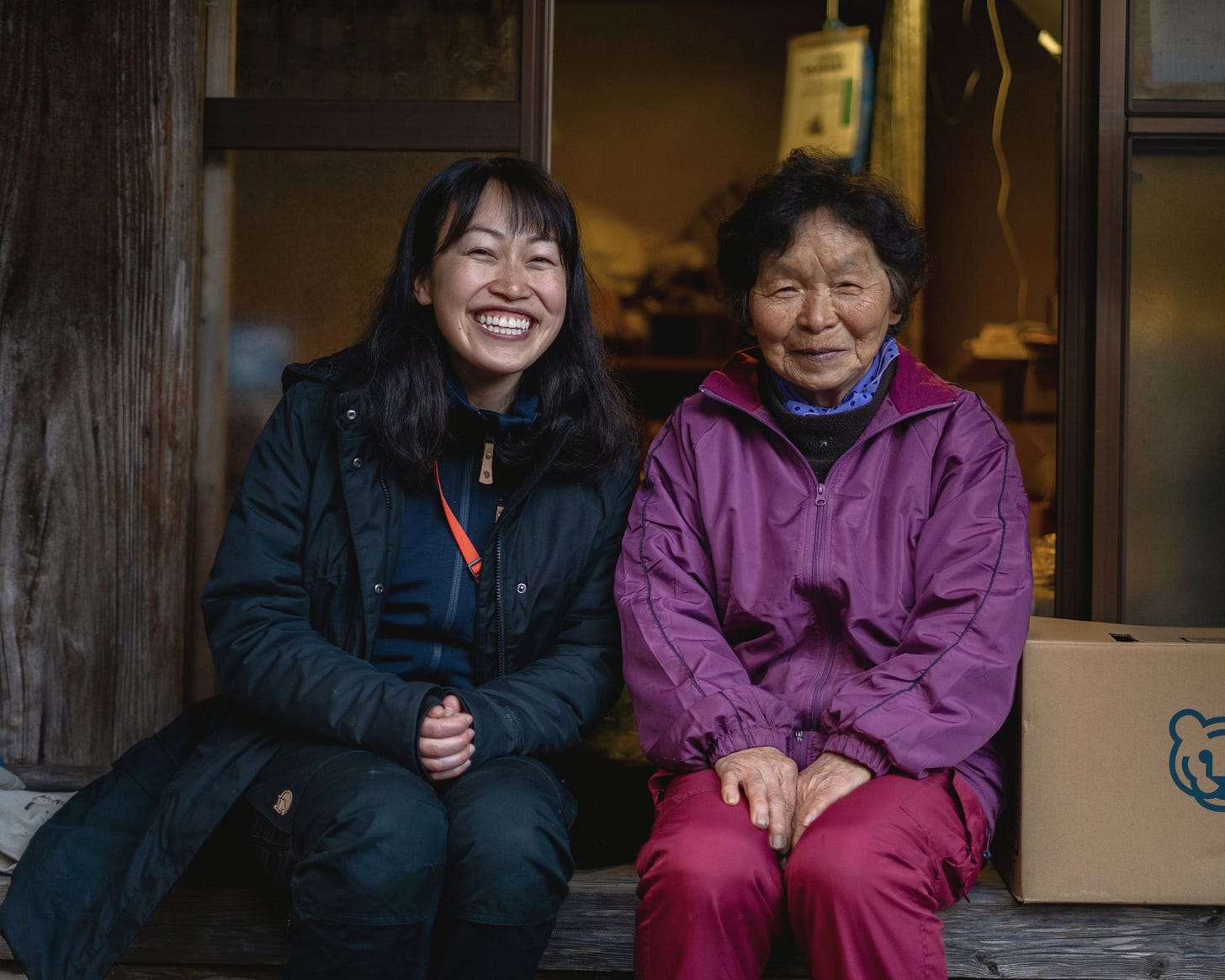

Kancha is currently only made by one grandmother, Akemi Ishimoto-san. When she welcomed us to her village last year to observe and help make tea, she immediately made us feel at home and said to us, “please, please, call me ‘kancha baa’chan’ (kancha grandma)”.

Along our 2.5-hour road trip from Kamikatsu to Kuo village, we drove along the coast of Shikoku Island. Although both Kamikatsu and Kuo are located in Tokushima prefecture, traveling from mountain to mountain is difficult, requiring a roundabout detour along the sea. As we wound along the coast, the ocean stretched endlessly. Seeing the ocean felt so expansive—the contrast to my daily scenery was incredibly refreshing. But when we arrived in Kuo, the landscape pulled inward again into terraced tea fields and mountains.

I stepped out of the car and scanned the wide terraced landscape of tea bushes. Searching for her was impossible since I knew her small frame would be hidden among the tea bushes. I called out, “Ishimoto-saaaan!” A moment later, a warm, familiar voice echoed back, “Kana-chaaan!”

Memories of her story and her quiet resolve to keep making kancha flooded back, and I felt a swell of emotion—I was incredibly grateful for the chance to return.

I wasn’t expecting to feel so at home moments after arriving, in a place I’ve only visited twice, for a total of no more than four days. But sometimes, feeling ‘at home’ isn’t measured in days but in the impression a place—or a person—leaves on you. How many homes have I felt in this lifetime already?

Maybe it’s also the way the mountains in Kuo feel so similar to Kamikatsu. The way the sky feels connected to the mountains, the mountains to the forest, and the forest to the stream. You can see the whole ecosystem in movement, and there’s something deeply familiar about this kind of mountain environment. The air is crisp and fresh, and hawks glide gently above the treetops.

Even in Kamikatsu where I’m enveloped in nature, I can fall into a routine and forget to observe. These days, it feels like you can connect to cell service from anywhere in the world. But, delightfully, Kuo is not one of those places. The moment we approached the village, my signal dropped.

There was a brief moment of panic—‘did I reply to that message?’, ‘I should have checked my email’, ‘I forgot to do that one thing.’ But then, the feeling passed, and my phone became nothing more than a camera. Even that felt like a bother to take out. It was delightfully easy to forget about the phone altogether. And in those moments, it became much easier to feel present.

What is kancha?

Last year, I described the tea but didn’t go into detail of how it’s prepared so I’ll share more about the step-by-step process if you’re interested in learning more!

Kancha 冬茶 is known as winter or cold tea. This rare tea is not well-known and is hardly drunk outside of this specific mountain area in Shikoku Island. It’s a folk tea or a tea that was traditionally made for local consumption. Unlike most teas in Japan that are harvested in spring, kancha is harvested once a year between mid December and until early March in the coldest period of the year.

For decades, Ishimoto-san has been trying to preserve kancha. Over 30 years ago, at the beginning of her tea-making practice, she founded the Shishikui Kancha Production Association, bringing together mostly women farmers to help with harvesting and production. Meeting her again, I asked her about those days. She told me that making tea with many people was some of her happiest memories. It’s bittersweet to hear these nostalgic reflections, as today, Ishimoto-san is the only one keeping the kancha tradition alive.

Picking Tea

While most commercially produced teas are made almost entirely by machines, kancha is labour-intensive, with nearly every step done by hand. While picking leaves one by one is meticulous, there’s a quiet joy in the repetitive slowness of the process.

Unlike awa bancha, where almost any leaf can be used, kancha demands more attention. Ishimoto-san selects each leaf individually, ensuring none are torn or discolored.

Sorting and Steaming

Her attention to detail continues as she carefully sorts through her baskets, inspecting the leaves once more—removing twigs, seeds, or anything that isn’t a beautiful deep green leaf.

The selected leaves are placed into a net bag and set inside a large steaming basket. Unlike awa bancha, which is boiled, kancha is steamed for about 25 minutes to stop the oxidation. During this time, the leaves soften and change into an olive, pale green. Ishimoto-san describes this color as kincha (金茶), a golden-yellow brown.

As steam rises from the basket, it carries the scent of brewing tea. The air fills with a soft, gentle earthiness.

Rolling and Resting

While the tea leaves are still warm, Ishimoto-san begins the rolling process. She once did this entirely by hand, but now uses a simple machine to partially roll the leaves. Rolling involves pressing and rubbing the leaves against each other to release their natural juices and oils.

She takes out the rolled leaves and continues to roll them gently by hand. She explains that during this step she talks to the tea and says, oishiku naa re (おいしくなあれ). “Be delicious, be healthy”, she wishes her tea. The rolled teas are placed in a wooden barrel overnight, which likely ferments them ever so slightly.

Drying Indoors and Outdoors

The last step of the process is drying the tea leaves. Ishimoto-san makes use of an unused greenhouse, which was previously built for another purpose but over time became abandoned. Since the weather can be rainy and cold, the greenhouse is a perfect place to keep her tea safe while it dries. Depending on the weather, this can take between 2-5 days.

The last essential step once the tea is nearly dry, is spreading the leaves under the open sky for a final sun-drying. “The sunlight improves the taste,” she tells me, “the tea receives the sun’s energy.”

I asked Ishimoto-san when this year’s harvest would end. “Around March 10th,” she replied, “but when I feel the first signs of spring warmth, I’ll stop for the season.”

Then she added, “kancha is most delicious at the winter solstice, when the days are coldest.” She paused, then asked me, “it must be the same with awa bancha, right? The tea must be best in the hottest months?”

Indeed, I’ve heard several awa bancha farmers say that tea picked in the peak of summer yields the best flavors. Last year, I wrote that kancha is yin and awa bancha is yang. While awa bancha thrives in the height of summer, kancha, by contrast, is made in the coldest days of the year. Two teas, shaped by opposing seasons, yet deeply connected.

Last year (2024), Ishimoto-san said it would be her last year of making tea, but I’m grateful she continued this year. When I said goodbye, I told her to stay healthy until next winter since I want to keep making tea with her.

My warmest thank you to all my friends from o5 Tea Company for making this tea-adventure possible.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, I’d love to hear from you. Would you like to try kancha or awa bancha? Your comments always warm my heart!

P.S. 🌱 I’m offering a small spring sale—25% off for new paid subscribers, now until April 1, 2025! 🌱 If you’d like to receive a spring-themed postcard, join me before then.

Your support means the world to me, but no matter how you choose to be here, I’m grateful!! Thank you for making this space one of many small joys 💛

Thank you, and have a lovely week ahead!

Kana

Fascinating! I love the varieties of Japanese tea including sencha, houjicha and genmae cha but this is the first I've heard of kancha, so must try it next time I'm in Tokushima visiting my wife's family.

Thank you for this truly wonderful post! After bringing him tea as omiyage from Japan, my (Swiss) dad became a serious lover of Japanese green tea. He was intrigued, when he heard about Kancha and was wondering if Ishimoto-san is selling her tea to individuals too? (Shippment to a Japanese address ok)