'Yutori' for 2025

& Japanese rituals for the new year

Happy 2025 everyone!

I’m back in Vancouver, Canada, spending several weeks at home. It feels wonderful to return and spend time with my family.

Immediately I’m both caught off guard and completely smitten by the way everyone here seems to effortlessly fall into small talk. From grocery store clerks to cafe workers, there’s an ease in their interactions. The other day, while ordering coffee, the barista asked me (in such a warm and genuine way) if I had enjoyed my New Year’s Eve. Taken by surprise by the question, I replied, “It was quiet, and I enjoyed it.” Forgetting to reciprocate with an “And you?” I stood awkwardly as he smiled and followed up by asking me if I was looking forward to 2025. Flustered, I managed to say, “Oh… yes, very much,” and quickly added, “Have a great New Year!” before shuffling to the counter to pick up my tumbler.

Speaking of tumblers, I love that when I bring mine and order a coffee, it doesn’t seem to matter what size I ask for—the staff always fill it to the brim. It’s a small, trivial thing, but it feels generous or relaxed.

There’s a casualness to interactions in Canada that doesn’t come as easily in Japan. In the Japanese countryside, where I live, I feel a deep sense of community and connection, which allows me to be more myself. Yet, there’s always a feeling (or need because of the language) to maintain politeness. It can feel like a subtle pressure to always be formal, even in familiar spaces. Here in Vancouver, the casual, unscripted moments—like a barista asking about my New Year or a tumbler filled generously—feel like little gifts of connection.

Rituals as Anchors

Japanese have many rituals for the New Year because it is one of the most culturally and spiritually significant times of the year. Christmas comes and passes like an ordinary day, but the days around the new year are important for reflection. Most of the traditions are rooted in Shinto and Buddhist beliefs, as well as centuries-old farming & agriculture practices.

Many Japanese rituals emerged in a time when life was far more precarious. Harvests, whether bountiful or scarce, seemed beyond human control and were entrusted to the realm of kami gods. Yet now, in a world where life often feels more predictable—though perhaps not entirely, given the volatility of climate and politics—I wonder why we continue to hold onto these practices, traditions, and rituals.

But perhaps we need rituals more than ever. When so little feels certain, these traditions become anchors, giving us something solid to hold onto. They also connect us to our history and culture, urging us to honor the past while navigating into an unknown future.

Before New Year’s day, our family did an osouji (大掃除)—a “big cleaning” ritual to sweep out the old and welcome the new. My dad tackles the kitchen, unscrewing bolts to clean the ventilators, a task so daunting it feels suited an an annual affair. I’m tasked with the floors and instructed by my mom to put aijō (愛情) love and affection into each wiping stroke. My mom and sister pack away the Christmas ornaments to make space for kazari (飾り) the traditional Japanese New Year decorations.

We spend an entire afternoon searching for dust and wiping the tough corners that often get neglected, moving furniture around, and all the mundane and unglamorous tasks associated with cleaning. While we’re sweeping away, I don’t think any of us are taking to heart the apparent symbolism of our cleaning, but in the end, there’s a quiet gratitude and perhaps a lightness that comes when things are put back into place and dusted with aijō (愛情) love and affection.

Ornaments for the New Year (and for the gods)

In Japan, kazari, or (objects of) ornamentation, isn’t only about creating an atmosphere for the New Year; each object has a purpose and a deeper meaning.

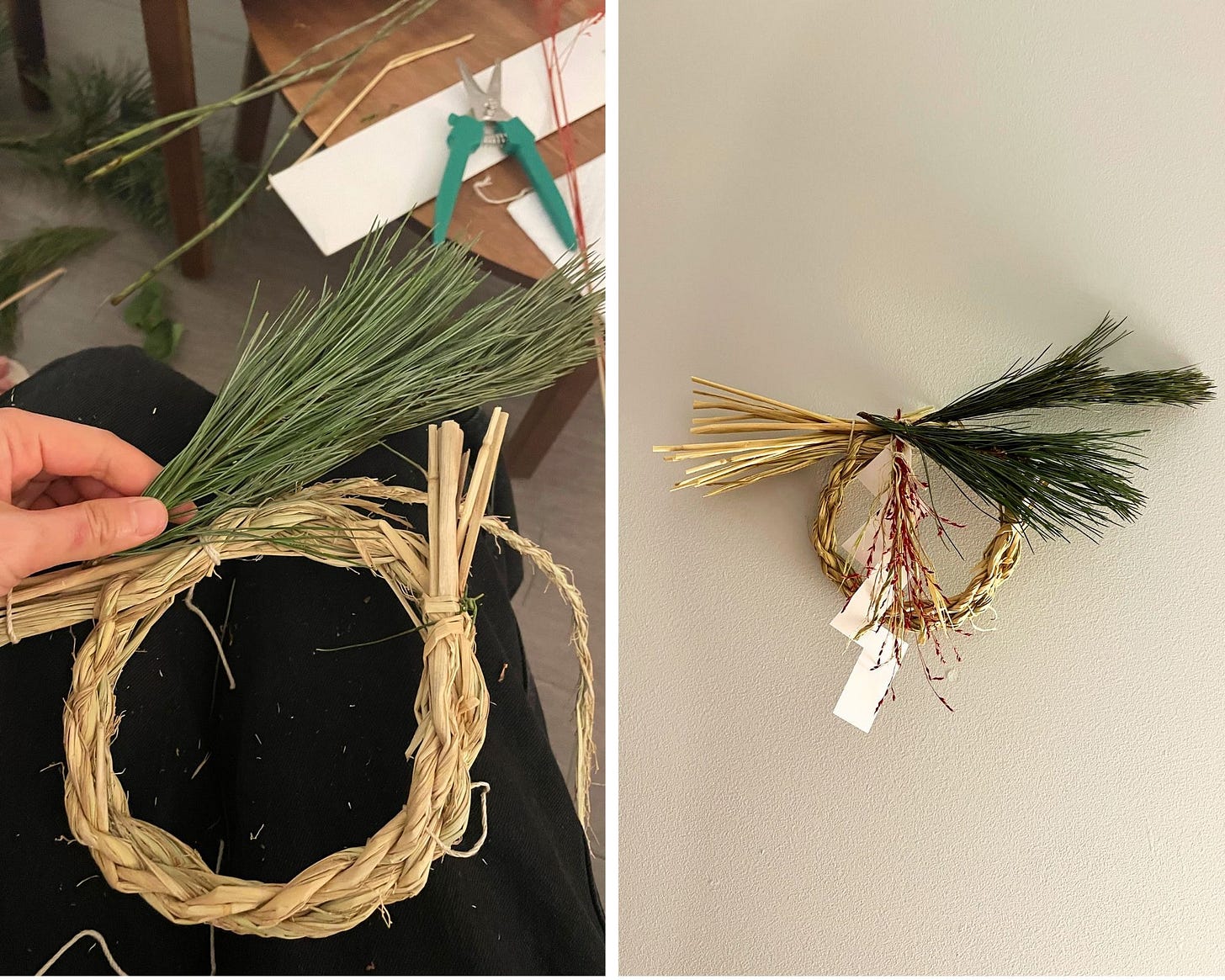

Shimekazari しめ飾りare the decorations often found outside front doors and temple gates—they are essentially the bridge to the world of gods. Shimekarzari are made with braided and twisted dried rice straws.

The process of braiding rice straw is something many may not have seen, and it’s incredibly slow and meticulous. Each twist is made between the palms of the hands—requiring a gentle yet swift motion while applying just the right amount of pressure to bind the two strands together. I’m in awe of the ingenuity of those who created with what was available to them and how that tradition lives on people.

Kagamimochi is a stack of two round rice cakes, one larger and one smaller. In the past, rice used for making mochi was highly valued, symbolizing its significance. The round shape of kagamimochi represents a mirror, encouraging reflection on the past year. Additionally, the two rice cakes are said to represent the moon (yin) and the sun (yang), with their union symbolizing a harmonious balance.

Yutori for 2025

I hesitate to take a Japanese word and distill its meaning into English—especially when it’s drawn apart from the context and its layered nuances aren’t explored. Words like ikigai (life purpose) or wabi-sabi (beauty in imperfection) are deeply philosophical, intricately tied to ways of living, and difficult to define standalone. We often tidy them up into neat packages of meaning, yet if you ask a Japanese person about their ikigai, they may find it hard to find the words to answer. But I’m making an exception to share a word I want to carry into the new year, and I invite you to join me.

Yutori is a noun that means having room to spare, not being cramped. Room to breathe. Rest. At its core, yutori translates to "spaciousness", and the concept extends beyond physical space, encompassing mental and emotional space as well. In all honesty, yutori is a concept my mom has tried to instill in me my whole life—but while in my 20s, I found it harder to grasp its true value.

The word yutori ゆとり has taken on special significance for me during my years in Kamikatsu. It’s a term I often hear when talking about happiness and a "good life" with others. But yutori is more than its translated meaning—it’s a feeling, a moment, a connection to the scenery around me. I think of standing amidst the mountain landscape, gazing at the terraced rice fields, watching long blades of grass sway like ocean waves in the wind—in those moments, we would say, yutori (or to have yutori ゆとりがある).

While the modern use of yutori in education and workplaces often refers to better work-life balance, reducing stress, or easing pressure on children in school, this interpretation feels incomplete. Instead, I find a deeper resonance in this quote by a Japanese Buddhist monk:

The Way of Life as a Human by Taido Matsubara:

"…Today we are far too busy. Everyone is swept along by something, and there is no longer the time to 'observe' things carefully, nor the space to reflect on our inner selves. A life filled only with the hustle and bustle, lacking in nourishment, feels unbearably lonely. I wish for the mental space to consider myself and care for others. This space, or yutori, is essential for a fulfilling life. In that space, we should deeply contemplate how we should live."

Yutori in the context of Kamikatsu is the way the word becomes alive in the presence of nature. It’s a reminder that the pursuit of space, whether in our minds, our hearts, or our physical surroundings, is not just about the absence of noise or activity but the presence of something deeper: a space for thought, connection, and being. I believe it can be felt by anyone who yearns for more space in their life.

Original poem in Japanese:

『人間としての生き方』(松原泰道)より、

それにしても現在は、あまりにも忙しすぎます。みんな何かに振りまわされ、ものごとをじっくり「観察」するゆとりもなくなっていますし、自分の内面を見つめる余裕もなくなっています。

潤いのない、ぎすぎすした多忙なだけの人生では、あまりにも寂しすぎます。自分を考え、他者を気遣うだけの心のゆとりをもちたいものです。

ゆとりは、人生の充実のためにあります。ゆとりのなかで、自分は何のために生まれてきたのか、どう生きるべきかを大いに思索すべきでしょう。

Have a beautiful 2025—may it be extra spacious 💛

With love,

Kana

You as well!! Happy new year 🍃🍵

Thank you so much for this beautiful reminder to leave breathing space for ourselves, Kana! I'm thinking of the movement of an active sourdough starter and how there should always be plenty of space within the container so it doesn't burst and overflow; similarly, I'm reminding myself to create space (time) in my own 'jar' of life to grow, rest, and reflect so I can adapt as I need! <3